In 2023, the ATW participated in the Virtual Writers in Residence program, organised by the UNESCO Melbourne City of Literature office. This initiative connects global City of Literature writers with ten Melbourne-based organisations throughout the month of November to create residency outcomes and connect with Melbourne as a City of Literature. The first of three pieces, our Virtual Writer in Residence, Kate Robinson responded to the tapestry, 'Everything has two witnesses, one on earth and one in the sky' designed by Sangeeta Sandrasegar and woven by Sue Batten.

Weaver, Sue Batten, compares contemporary artist Sangeeta Sandrasegar’s work, Everything has two witnesses, one on earth and one in the sky, to earlier tapestries showing images of ‘horrendous exploitation of the environment’.1

She cites the fifteenth century Devonshire Hunting Tapestries, for example, where a bear bitten by slavering dogs curls in pain while a man aims his sword for the kill; a woman points in the direction of prey; a hunter routs out bear cubs with a club; two men flay a boar. Or the sixteenth century Hunts of Maximilian - also commissioned to adorn high- status walls in Europe - where depressed, bedraggled, maltreated dogs drive terrified deer into a lake to drown.

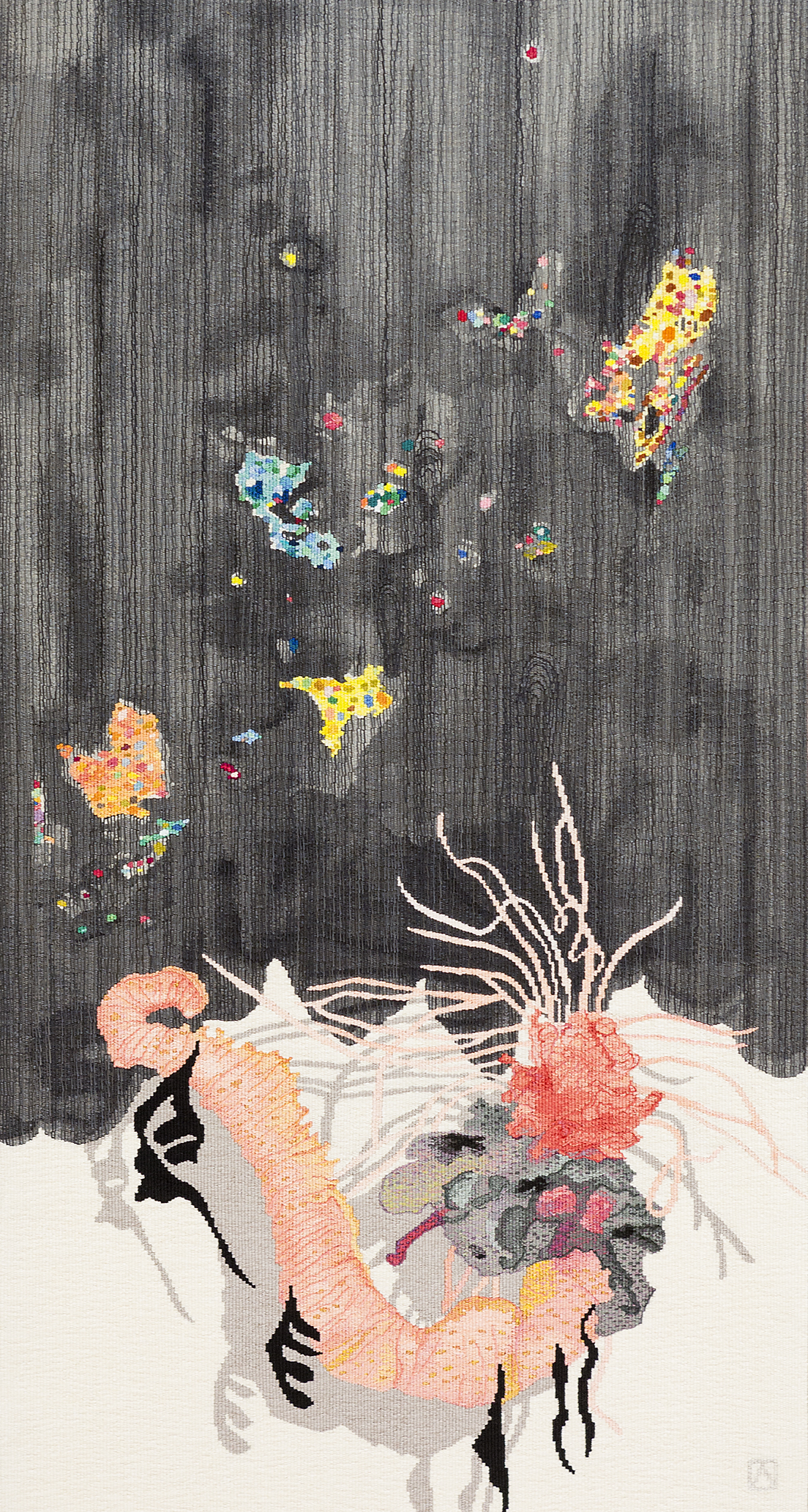

Sandrasegar’s piece, a design commission for the Australian Tapestry Workshop, shows an image of the ocean invaded by man-made pollutants. However, unlike its earlier comparisons where tasselled white men and women gloat, goad or participate in the hunt, the dark domain of Sandrasegar’s tapestry is redeemed by the glowing presence of a sea worm. Everything has two witnesses, one on earth and one in the sky explores the sustainability of the oceans, asking ‘what a future Commonwealth might hold for the multiple identities emerging from a colonial and indigenous past’. Sandrasegar, an artist of Malaysian, Indian and Australian heritage, talks of empires and colonial power and how oceanic travel was a means to domination. She talks about Australia’s long history of migration, its constant story of travel and trade. She speaks of the idea of water coursing, of the idea of weaving and water flowing together. She imagines future myths in which mermaids are transformed from porpoises.

In another of her works, she spins and weaves with them still, and continues to hang, Sandrasegar explores female mythic personifications of weaving such as the Greek, metis, and the Latin, texere, equating ‘the process of sewing and weaving simultaneously to the act of speech and the working of fabric’. Through the materiality of weaving the processes of time, communication and motion connect.

For every square kilometre of water around Australia there are 4000 particles of plastic micro-beads, says Sandrasegar. Plastics are made of chemicals that can’t break down thus leaching into the water. Since pollutants in the ocean do not respect boundaries and ecological degradation can travel anywhere, our ‘commonwealth’, she suggests, is global contamination. In Everything has two witnesses, one on earth and one in the sky, colourful fragments of plastic descend through a blackness of the ocean, making a map of the commonwealth countries. At the tapestry’s base a sea worm, tentacles of pink emanating through the sea like an explosion, is frustrated and embattled.

Sea worms, industrious marine-farmers, burrow deep through the sand of the ocean’s floor, oxygenating the water. They heal pollution naturally, breaking up oil spills. But the worms can’t digest plastic micro-beads. And so, as the pink, gold luminescence at the base of Sandrasegar’s tapestry shows, tragically, the sea-worm’s ecological industry is thwarted. Black oil, shaped like Matisse cut-outs, falls from the worm, doubled in the shadow that surrounds it.

The shadow, itself, woven into the sandy whiteness of the ocean floor is a statement, says Sandrasegar, of hybridity, situating the ecological sea-worm-subject within the context of blackness and whiteness, race and globalisation. Or we could see it as a Jungian shadow: the ocean and the worm a symbol of our own (unconscious) connection with nature, or the unconscious being of nature herself.

Batten has woven the work with an open and free-flowing yet meticulous and luminous precision. The dark ocean, a descending lacy filigree in the subtlest tonal range of greys, provides a visual foil for the colours which explode like colourful jewels, sweeties, delectable morsels to visually tempt the eye; the shadow she has woven, all the more powerful for its simplicity and delicate understatement.

The title of the work comes from David Mowaljarl, a Ngarinyin Elder from the Kimberley region in Western Australia. It is the Kulin Nation - the Wurundjeri, Boonwurrung (Bunurong), Wathaurrung, Taungurung and Dja Dja Wurrung - which has inhabited the Land, traditionally called Naarm, where the young city of Melbourne and the Australian Tapestry Workshop now exists, for at least 35 to 40 thousand years. For the Boonwurrung (Bunorong) the Land' has always been a sacred place and it always will be.' 2

Stargazers, Ngarinyin constellations relate the heavens back to the earth, the whole of it is represented in both the soil and in the stars, and so: Everything has two witnesses, one on earth and one in the sky.

The witnessing of the sea-worm, swimming in the deeps of the southern hemisphere, is mirrored in a commonwealth constellation of plastic debris falling through the blackness of the sea, itself becoming a map of the earth witnessed from outer space. On the other side of the planet, Scottish Barbadian artist Alberta Whittle, engages with ideas of the Caribbean Gothic in her exhibition Even in the most beautiful place in the world, our breath can falter. Tropes of the heavens appear in titles of her paintings: Autumn Equinox - abolition invocation; Autumn Equinox - Awakening; Under the full moon, I am born anew.

Whittle explains her creative practice is motivated by ‘the desire to manifest self- compassion and collective care as key methods in battling anti-blackness’.3

Meditating on Ten Poems of Kindness by poet and playwright, Jackie Kay, before beginning work on the exhibition, Whittle brings a poetic sensibility to tragedy, mapping a territory in which seemingly irreconcilable opposites are brought into creative relationship.

Her paintings, exhibited in a brightly painted vivid pink, orange and lilac space, form a ring around the gallery which moves from a sense of isolation, youth and innocence in Muddy caresses at Dunloe Lane through maturation and confusion to a kind of resolution in Under the full moon, I am born anew and Only the sun was there to keep us company.

A central sculptural work, Ring around the Rosy, is made of metal and tapestry. The title refers to a nursery rhyme in which children holding hands dance in a circle; the last one to duck downwards on the final line goes into the centre of the ring.

The childlike quality of the words is belied by a creepiness of the rhyme. It has been used in horror films; it has been sometimes, if erroneously, associated with the bubonic plague; the last line is occasionally rendered ‘we all drop down dead’.

Made of wool, linen, cotton, cowrie shells, children’s hair clips and crystal, the tapestry was woven at the Dovecote Studios in Edinburgh while the powder-coated steel gates from which the cloth is suspended were fabricated at the Glasgow Sculpture Studios.

The green gates are decorative, embellished with stylised roses referencing the roses of Glasgow’s Charles Rennie Mackintosh, architect of the city’s iconic Art School, twice burned in a devastating fire and now propped up in an iron lattice of scaffolding, undergoing the precarious work of reinvention.

On entering the gallery, you are first of all confronted with the tapestry’s tangled back. It is woven in such a way that you can see the tapestry’s edges which are not rectangular but irregular and rounded like a multicoloured blob that seems both splayed against and trapped by the gates. The vertical red warp strings are plaited together like long pigtails of hair. The warp-hair drapes down over the gates and snakes onto the floor ending in loops and coils in which are secreted totemic objects, crystals and shells, creating an uneasy visual tension and begging the question of whether it is the upright metal gates or the bendy scarlet plaits that are the real ground of the work.

Woven in a rich, warm palette of oranges, pinks, browns and reds contrasted with blues, greys and turquoise the tapestry is a blaze of colour. At the top, on the front side, the Dovecote’s logo and the initials of the weavers: NR, AW and EJW.

Primal painted faces stare out. They grimace, smile, peer, leer, tricky to decipher. Sad? Threatening? Angry? Confused? Shy? Gleeful? The eyes seem human but they might be masks and they might be masking something non-human. The face/masks appear from amidst donut rings and organic forms, maybe a landscape of rivers and hills, maybe bodies, arms reaching out in a ring. Across it all: the words ‘Ring Around The Rosy’ in ivory tones. The words are jaggy and childlike, like someone saying ‘boo’. The labour, time and materiality inherent in the tapestry is palpable, at odds with the seemingly off-the-cuff, sing- song text.

I chose to look at Sandrasegar and Whittle, two artists living and working on either side of the globe, because they are both engaged, amongst other things, with issues of migration, hybridity and colonialism and they have both expressed their thoughts through tapestry. The antipodean concept of a boomerang has been used in regard to colonialism by Foucault, Aimé Césaire, Hannah Arendt and others to envisage how the repressive techniques of colonialism will come back in time to bite the coloniser. What goes around, comes around.

Recently, historian Kojo Koram in his book Uncommon Wealth has invoked the boomerang of colonialism to explain trends of economic disparity in contemporary Britain, writing of the ‘financial tentacles’ that have grown over the centuries insuring there was ‘no great redistribution of wealth either at the global or local level.’4

His idea of ‘financial tentacles’ makes me picture the tentacles emanating from the glowing sea-worm battling with plastic. Ethicist, Nigel Biggar, meanwhile, critiques the concept of colonialism itself, talking of commonwealth in terms of ‘shared cultural ties and political interests’.5

Both he and Koram bewail the culture wars of which competing ideas of colonialism have become a key part, the former in terms of a dismissal of working class concerns, the latter from the perspective of domestic self-confidence.

Although both writers come, in certain respects, from different places within the political spectrum, they both decry cancel culture where talking about colonialism is shut down, its complexities shunned. For Koram, this means the focus is on micro-aggressions instead of ‘wealth inequality or urban deprivation’.6 For Biggar, it has the potential to undermine and unravel a hard-won liberal democracy.7

The work of holding opposites in creative tension is a fundament, it seems to me, of weaving. The uneasy traction of Whittle’s work, exemplifies the personal, internal and yet shared processes that this entails. Sandrasegar’s beautiful sea-worm, a reminder of the consciousness of nature in the ocean’s depths - invisible from the surface, yet indispensable to the planet’s health and wellbeing. Weaving’s warp and the weft go in opposites directions and yet together they create. What is woven shows that what is in opposition doesn’t have to cancel or compete, it completes.

1. https://www.sangeetasandrasegar.com.au/Everything-has-two-witnesses. Everything has two witnesses, one on earth and one in the sky, 2014, 164 x 89 cm wool, cotton.

2. https://nepeanhistoricalsociety.asn.au/history/pre-history/

3. http://www.albertawhittle.com/biography.html. Even in the most beautiful place in the world, our breath can falter, The Modern Institute, Glasgow, 2023.

4. Koram, Kojo, Uncommon Wealth, Britain and the Aftermath of Empire (John Murray, 2022) 217

5. Biggar, Nigel, Colonialism, A Moral Reckoning (William Collins, 2023) 16

6. Koram, 11

7. Biggar, 215