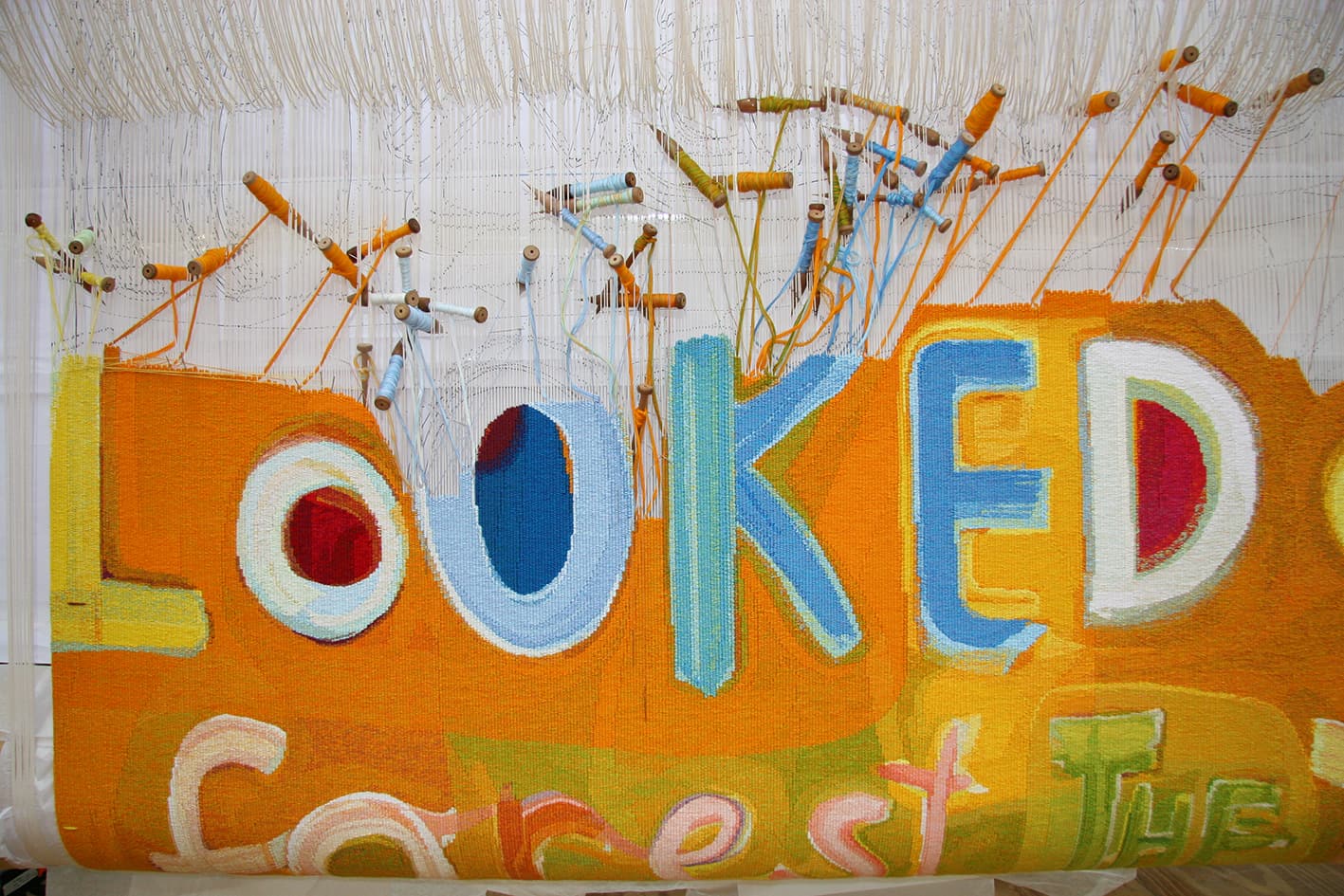

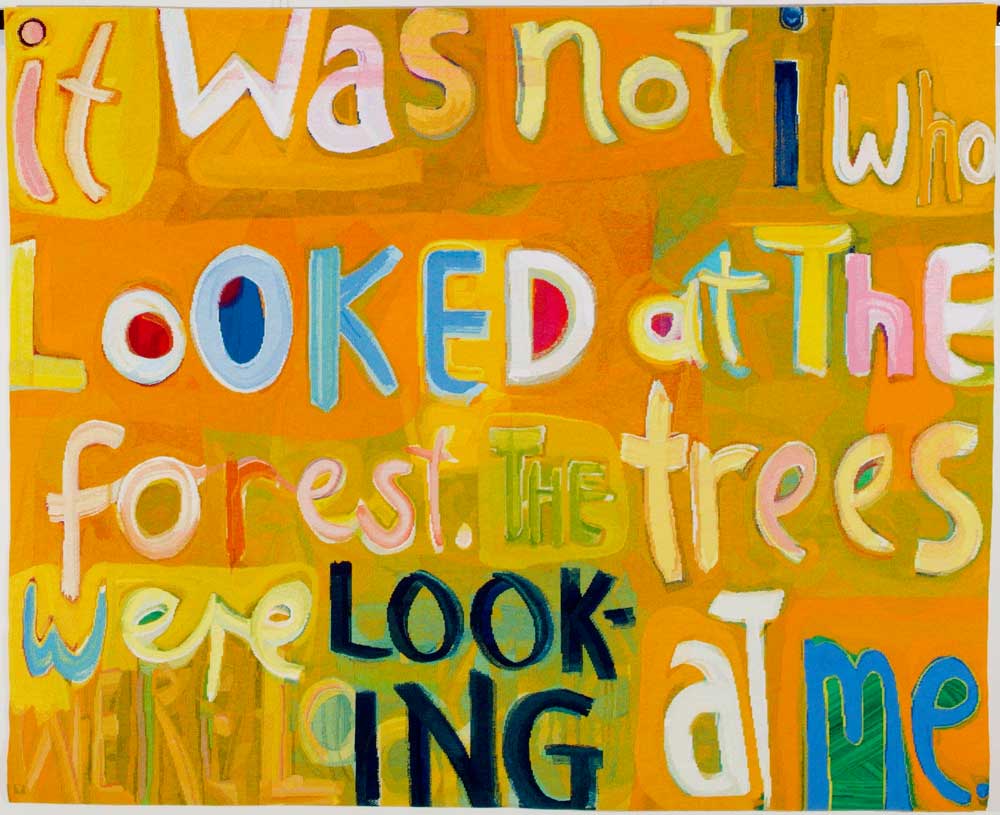

In 2006 Angela Brennan’s design It was not I that looked was translated into tapestry by the ATW.

The enigmatic title of this tapestry is taken from the 20th-century modernist painter Paul Klee. In one of his journals, Klee wrote, “it was not I who looked at the trees, the trees were looking at me.” Brennan exercises a textual slippage by swapping the word “trees” for “forests” and turned the whole wry phrase into an extroverted and playful painting. The eccentric letters, unmatched fonts and cursive script march across the canvas in an almost musical fashion. The letters are no longer simply part of a lifeless alphabet, but seem to wobble and gyrate as if they themselves are animate beings.

Brennan was intrigued by the process of translating the painting into tapestry. She visited the Workshop several times during the weaving to see the preliminary samples, and to suggest adjustments for colour mixing and scale. For Brennan, the developing tapestry took on the sense of a new life. Brennan noted, “I was fascinated to see the work unfurl before my eyes, emerging independently from its original source.”

The weavers involved in this project were intent upon retaining the gestural quality and energy of Brennan’s painting. In doing this they did not aim to imitate paint, but instead give the shapes a robust weaving feel, with stepped edges and mixed colour in the right areas. The palette is limited with colours repeated throughout the work, giving a sense of unity to the whole.

Brennan’s work is housed in numerous public and private collections both in Australia and overseas. She is represented by Niagara Gallery.

Let me put my love into you, designed by Nell, was translated into tapestry by the ATW in 2006.

Nell's practice is concerned with life and death, viewed as processes of growth and evanescence. Her vocabulary of motifs – which includes eggs, fruit, mice, reptiles, lightning bolts, precious metals, ghosts and gravestones – become symbols of sexuality, seduction, reproduction and transformation within the work.

When granted the commission, Nell was based in Paris and undertook research for the design in the major tapestry collections of the French workshops. The motifs in the design form an allegorical image: eggs symbolize both nurturing and fragility; and the snake and apple simultaneously suggest temptation and fallibility, and the possibility for change and rebirth. The original artwork for Let me put the love in you is housed in the collection of Deutsche Bank, Sydney.

Nell frequently visited the ATW throughout the weaving process, allowing the project to be a true collaboration between artist and weavers. Two of the main challenges of the project were finding the right black tone for the background area, which needed to be strong and flat; and providing the right "support" for the two main images. The snake needed to appear clear and sharp against the black of the background, while remaining organic and fluid. The design and palette are reminiscent of medieval tapestry design.

The tapestry was woven on a broad warp setting, allowing tapestry qualities, such as the stepped line, to feature quite strongly.

In 2006 weavers of the ATW had the pleasure of interpreting Glyphs, designed by G W Bot, into a tapestry spanning 1.9 m x 3.97 m.

G.W. Bot is a contemporary Australian printmaker, sculptor and graphic artist who has created her own signs and glyphs to capture her close, personal relationship with the Australian landscape. Her artist’s name derives from ‘le grand Wam Bot’—the early French explorers term for the wombat, which she has adopted as her totemic animal.

G W Bot is represented by Australian Galleries in Melbourne and Sydney.

Circus V, designed by Ken Whisson in 2006, was woven to celebrate the contribution to the arts made by Sir Rupert Hamer, former Premier of Victoria and Minister for the Arts.

Born in 1927, Whisson is a distinguished Australian artist. Whisson created the painting Circus V in early 1985. It is typical of his work, in that it simultaneously imparts a sense of spontaneity and order, based on the subjective stimuli of memory and intuition.

The ATW (formerly known as the Victoria Tapestry Workshop) was established by the Victorian Labour Government in 1976, following a feasibility study commissioned by Sir Rupert when he was Victorian Arts Minister. The tapestry was woven to be a major feature of the National Circus Centre — a project close to Sir Rupert’s heart, and one he worked passionately to raise funds for up until his death in 2004.

Throughout the translation process, the weavers sought to emphasize the dynamic linear qualities of the painting. The limited colour palette offered many subtle shifts and changes. The overall feeling of light was important to the tapestry design and great care was taken in the selection of white tones used throughout the background.

Open world, designed by John Young in 2005, was commissioned by the State Government of Victoria as a gift from the people of Victoria to the people of Nanjing in China, marking the 25th anniversary of the sister-city relationship between Nanjing and Melbourne and to celebrate the completion of the then new Nanjing Library.

Young, who was born in Hong Kong in 1956 and moved to Australia in 1967, explores his own artistic and cultural history through his practice, while responding to issues in Australian art history.

Open world is a composite image incorporating Australian and Chinese references. The background is of an 18th-century Chinese tapestry in reverse, depicting foreigners offering gifts to a Chinese ruler. A cluster of photographic imagery lines the edges of the tapestry: a Eurasian women in a Chinese wedding dress; Victoria’s Great Ocean Road; a cloudscape; and pictures of the cherry blossom (native to Nanjing province) and pink heath (Victoria’s floral emblem). The surface is dotted with Chinese calligraphy and the names of lands discovered by the 15th-century Chinese explorer, Admiral Zheng He. The Chinese characters layered over the top of the design are previous historical names for Nanjing. Young arranged for these names to be written by a Chinese calligrapher in the appropriate script for the historical period in which the name was used. There are also three words in English mirroring the Chinese, Kulin Nation, Naarm and Bareberp, which are all Aboriginal/Koori names for Melbourne/ Victoria.

In its bicultural references Open World continues to examine Young’s evolving exploration of transcultural concerns and the diasporic experience.

Pedro Wonaeamirri was born in 1974 on Melville Island, the larger of the Tiwi Islands, off the coast of Darwin in the Northern Territory. He lives in the remote community of Milikapiti (Snake Bay). In 2005 the ATW translated Wonaeamirri’s design Pwoja Pukumani body paint design into tapestry.

The imagery of pwoja body painting designs and his carved Pukumani poles are the artist’s link to the traditions and future of the Tiwi people. Tiwi art is derived from ceremonial body painting and the ornate decoration applied to Pukumani funerary poles, Yimawilini bark baskets, and associated ritual objects made from the Pukumani ceremony. Traditionally, deceased Tiwi people are buried on the day they pass away, but the Pukumani ceremonies are performed six months to several years after the death. Over the years, Wonaeamirri has developed his own style. Unusually, he has chosen to use a traditional wooden comb, giving his paintings a stylized look, whilst continually experimenting with combinations of blocks of ochre background and intricate pattern. Wonaeamirri is also well known for his Pukumani pole carvings. He says much of his inspiration comes from childhood memories of watching the elders paint and carve their designs.

Pwoja Pukumani body paint design is the second tapestry to be commissioned by the Tapestry Foundation of Australia, as part of the Embassy Tapestry Collection and was supported by private donations.

Pedro Wonaeamirri is represented by Alcaston Gallery, Melbourne.In 2005 the ATW completed work on Forest Noise, designed by Ian Woo, in preparation for an exhibition to be held at Singapore Tyler Print Institute entitled The Art of Collaboration: Masterpieces of Modern Tapestry.

Singapore-based Woo’s abstract paintings are characterized by both their visual complexity, and also paradoxically by their simple thoughtfulness. Woo frequently alludes to the everyday, visually depicting gestures, transient moments and thoughts.

Speaking of the design, Woo noted that it “is a kaleidoscopic work informed by fractured compositions of paint and text activities that simulate disturbances in the midst of the painting’s horizontal suspensions.”

The design for Forest Noise incorporates fractured sections of text juxtaposed against more organic imagery. It seems that it is the ‘clash’ or opposition of forms that conveys Woo’s investigation of the “memory and essence of the forest… and the city,or the differing sounds, memories and sensations of urban and natural space.”

Abstract Sequence, woven in 2004, was created to be added to the suite of tapestries that Roger Kemp designed for the Great Hall in the National Gallery of Victoria.

Kemp was one of the earliest artists to work with the Tapestry Workshop. His visual language of symbolic forms made for a dynamic translation into tapestry. Kemp’s tapestry Images was commissioned in 1978 and acquired by the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) in the same year. In 1984 he designed the tapestry Evolving forms, commissioned by the NGV to hang in the Great Hall.

Evolving forms became the first in a suite of three tapestries designed by Kemp for, and conceived as a response to, the Great Hall and its extraordinary faceted glass ceiling designed by Leonard French. Both artists' works harmonise: the broad steel trusses of the vaulted ceiling, with its bright glass, find an echo in the charcoal bands that delineate the abstract forms and jewel-like colours of ruby-red, turquoise, lilac and amethyst-pink in Kemp's tapestries.

The three tapestries demanded varying technical approaches. The first tapestry, Evolving forms, was soft in colour and approach. Weaver Cheryl Thornton notes, 'It was only when it was installed in the Great Hall that we discovered the high viewing distance made the tapestry read as a painting. For the next tapestry in the suite, Piano movement, we decided to accentuate the work's medium as a textile. We did this by exaggerating the stepping - the movement up and across the warp threads... which created the effect of a rougher, more jagged surface, giving the work more of a textile feel.”

The third tapestry, Organic form, was slightly more subdued and provided a visual balance to the contrast of the preceding two works. Kemp was actively involved in the translation of the first two works, but died in 1987 before Organic form was complete.

Abstract sequence continues the composition and themes of the previous works. By this stage the weavers not only had extensive knowledge and technical expertise to undertake the translation, but also a great awareness of Kemp's artistic sensibility. Thornton noted that when you worked closely with Kemp's mark-making, you can see that “These marks resolved the whole painting. Abstract sequence and Unity in space were a reminder of what a great artist Kemp had been: it was humbling to work with an artist of his calibre.”

Roger Kemp was a major contributor to the development of abstract painting in Australia. His work is housed in major collections in Australia and overseas.

Daisy Andrews comes from the remote Aboriginal community at Fitzroy Crossing in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. She was born at Cherrabun Station and belongs to the Walmajarri people. In 2004 the ATW translated her painting, Lumpu Lumpu country, into a tapestry.

The country of Lumpu Lumpu is Andrew’s ancestral terrain, but her family were already displaced when she was born. Stories about the land were narrated to Andrews by her parents and grandparents, but she only visited the area later in life. Her family, driven out by dispossession, were too traumatised to return. Andrew's paintings, drawings and prints of Lumpu Lumpu are made as memorials to her homeland.

The tapestry Lumpu Lumpu country captures the drama of the landscape with its cliffs and valleys, wildflowers and blazing red earth. The carpet of purple flowers finds a visual echo in the lavender coloured sky, and the whole image is suffused with sentiment. Andrew states “when I draw my picture I am seeing that good country in my head, looking at those sandhills, flowers, everything was very good. I think hard when I look at my country. I think how I have to paint it. I look hard, it makes me sad too, it is beautiful, good country, but it makes me sad to think about all of the old people who were living there.” [1]

This tapestry was the first tapestry produced for the Embassy Tapestry Collection and is currently on loan to The Australian Embassy in Tokyo. Lumpu Lumpu country, was commissioned by the Tapestry Foundation through the support of a number of private donors.

Since 1991 Andrews was an active member of the Mangkaja Arts Centre. Andrew’s work has been exhibited and housed widely in national and international collections.

The ATW was saddened to hear of Daisy’s passing in 2015 and hopes that her tapestry can exist as a legacy to her life story.

[1] Daisy Andrews, quoted in the Victorian Tapestry Workshop Newsletter, Vol 1, Issue 16, October 2004.

In 2004 the ATW wove Gulammohammed Sheikh’s Mappamundi — a design composed from a melting pot of Eastern and Western history, juxtaposed on an image of a map— visual components that are now synonymous with Sheikh’s wider practice.

Sheikh’s fascination for painted maps was triggered by a picture postcard he found in the British Library bookshop of a 13th-century map of the world, known as the Ebstorf Mappamundi. When Sheikh learned that the original parchment map was destroyed during the allied bombing in World War II, he used the image as inspiration for making his own world maps. Over five years Sheikh created approximately 15 versions of Mappamundi, each a celebration of Eastern and Western culture, history and contemporary events. His Mappamundis& feature stylistic influences, ranging from Ambrogio Lorenzetti and Piero della Francesca to Mughal painting, and contain a medley of Hindu and Muslim references to religious ritual, family customs, Indian village life and contemporary events, such as the destruction of the Bamyam Buddha in Afghanistan. The Mappamundi tapestry depicts the map framed in each corner by the symbolic figures of Mary Magdalene reaching out to Christ, Kabir weaving the shroud, Rama chasing elusive deer and a mad mystic, dancing. By an uncanny coincidence, the dimensions of the finished tapestry resemble those of the original, lost Ebstorf Mappamundi.

Gulammohammed Sheikh has exhibited widely in major international institutions.

To honour and celebrate Danish architect, Jørn Utzon’s design of the Sydney Opera House, the ATW translated Homage to Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach into a monumental tapestry, spanning 2.67 x 14.02m, in 2003.

Utzon (1918–2008) was the designer of Australia’s most distinctive national icon, the Sydney Opera House (SOH). He won the tender for the Opera House in 1957, but the project was besieged by political wrangling, budget overhauls and compromises to his design resulting in Utzon’s resignation before the building’s completion in 1973. Later acknowledged as the creator of an architectural masterpiece, he was awarded a Hononary Doctorate from the University of Sydney in 2003 and in the same year received a Companion of the Order of Australia, as well as architecture’s most prestigious international award, the Pritzker Prize.

As the interior of Utzon’s original design had never been fully realised, he was recommissioned in 2000 to oversee a redevelopment of the building’s interior. The first space to be redesigned to Utzon’s specifications was the Reception Hall, re-named The Utzon Room, in his honour. The venue features the tapestry Homage to Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach, inspired by CPE Bach’s Hamburg Symphonies and Raphael’s painting Procession to Calvary. The tapestry derives from a collage featuring torn strips of coloured paper writ large into floating forms that take on an architectural dimension. Against the pale-blonde timber floor and walls, the tapestry glows with vibrancy and movement. The shapes tumble across the length of the work in an almost musical configuration: like a notation of syncopated acoustic elements forming point and counterpoint over the picture plane.

Due to the large scale of the tapestry, the weavers wove the design on it’s side.

The SOH was declared a World Heritage Site on 28 June 2007. Utzon became only the second person to have received such recognition for one of his designs during his lifetime.

To celebrate the Melbourne Cricket Ground’s 150th anniversary, the Melbourne Cricket Club tapestry, designed by Robert Ingpen AM was woven by the ATW in 2002.

The monumental tapestry, measuring 2.00 x 7.00m, depicts key members of the Melbourne Cricket Club (MCC). Placed in chronological order, the figures depicted range from the MCC’s first president, Frederick Powlett, to champion Australian batsman-keeper Adam Gilchrist and Socceroo Kevin Muscat, who kicked Australia’s only goal in its 1-0 victory over Uruguay in a 2001 World Cup qualifying match.

Included are some of the greats of football and cricket, memorable sporting events such as the 1956 Olympic Games and Austral Wheel Races and other notable occasions like royal and papal tours, Billy Graham’s Crusade and the performance by the Three Tenors.

Ingpen painted the figures individually and then painted a broader yellow / orange canvas, allowing the weavers to position the figures as the tapestry developed on the loom.

The tapestry hangs proudly outside the Long Room at the MCG, where members and visitors can admire and identify those who have made a significant contribution to what the MCG is today.

Robert Ingpen is represented by Melaleuca Gallery in Victoria.

Reg Mombassa playfully captured Sydney suburbs in his design Bush suburbs, which was translated into a tapestry by the ATW in 2002.

Mombassa (AKA. Chris O’Doherty) is a painter, printmaker and designer well known to Australian audiences, not only through his design work for the lifestyle label Mambo but also as a former member of the band Mental As Anything. His imagery depicts suburban environments and the outback as well as iconic Australian views such as backyard barbeques. Bush suburbs is based on an amalgam of suburbs in Sydney, and the scene reflects a charmed world of perfect order, each element merrily – if not comically – in its place. The stereotyped suburban bungalows are adaptations of the houses Reg remembers as a child that his father built.

The design for this tapestry was selected because of the qualities it shares both with the great tapestries of the past, and the grand mural paintings of Stanley Spencer (who also drew inspiration from medieval tapestries). The flat picture plane, the firmly articulated graphic nature of the work, its decorative and narrative qualities, and its powerful representation of everyday life, have all made for a strong and moving tapestry on a mural scale.

Reg Mombassa is represented by Watters Gallery in Sydney.

Celebration, designed by David Larwill in 1999, was commissioned by the Government of Victoria and the Victorian Arts Centre Trust and gifted to Singapore’s Esplanade Performing Arts Centre (EPAC), to mark their official opening in 2001.

Larwill began painting in 1979. His joyful use of colour and form, and unique child-like freshness has seen him dubbed as one of the leading figurative expressionists in Australia.

EPAC desired a tapestry that would evoke a sense of celebrating the arts. The design needed to portray a powerful image, that would be eye-catching, taking into consideration that the tapestry would be viewed from a distance, hung in a large space approximately 3 metres from the floor. The resultant design sees the figures, that are synonymous with Larwill’s style, bursting forth from a vibrant red background.

The three weavers working on this project focused on maintaining the vibrancy and energy of Larwill’s original design. The tonal similarities of the design, provided through complex colour mixing, posed a challenge for the weavers. This difficulty was overcome by selecting more saturated shades of colour and playing cotton off against wool to create a surface texture. 13 strands of yarn were wound on each bobbin used.

Prominent British artist Patrick Heron designed five tapestries after visiting Australia in 1990, the last of which, 22 July 1989, was woven at the ATW shortly after Heron’s death in 1999.

Heron (1920-1999) was a prominent figure in 20th-century British art associated with the St Ives School, based in Cornwall and led by Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth.

Heron came to Australia in 1990 to undertake an artist residency at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and was enthusiastic about the translation of his work into tapestry. In total five tapestries were woven by the ATW, all based on small gouaches Heron painted specifically for tapestry interpretation. Heron died just before the tapestry 22 July 1989 was completed in 1999.

The design for 22 July 1989 was based on a small gouache painting created by Heron.

The original design has a fluidity of surface, derived from the material qualities of the water-based paint. Heron’s gouache works are often lightly executed, with loose, orbicular forms accenting the watery effects. In 22 July 1989 arabesques of vivid colours - orange, violet and viridian - suggest flowering shrubs like pimpernels and bell heather, native to the landscapes of Cornwall.

Heron relished the collaborative process of tapestry making, engaging in ongoing discussions revolving around colour, surface and scale. He delighted in the final outcome of tapestry production, making effusive statements as in a letter to the weavers of his first tapestry:

“I had never imagined you would be able to do something that was so subtle! It really is incredibly related to the gouache. In certain lights it is almost as if the water of the original was still moving about across its surface! I should love to do a number of other tapestries with you, now that I have seen what you are able to do.” [1]

Patrick Heron’s work has been collected by major public art institutions worldwide.

[1] Patrick Heron, letter to Anne Kemp and Barbara Mauro at the Victorian Tapestry Workshop, 18 December 1991, quoted in Artists' Tapestries From Australia 1976-2005, The Beagle Press, 2007, p.264.

Panjiti Mary McLean, an elder of the Ngaatjajarra Aboriginal community from the Western Desert region in Central Australia, designed Painting at Kalkutjara, which was translated into tapestry by the ATW in 1998.

McLean’s paintings represent quotidian aspects of her community life, topographic features of the landscape, as well as the flora and fauna native to Ngaatjajarra, for example, bush foods like the quandong fruit. She works in a figurative tradition, her canvases replete with densely packed imagery teeming with life. McLean’s paintings often feature masses of tiny figures which seem to populate a fecund landscape, often intertwined with animal tracks or fields of flowers.

In Painting at Kaltukatjara, five figures with out-stretched arms are interspersed over a red ground, strewn with white and yellow flowers. ATW Weaver Irene Creedon was keen to capture the expressiveness of the ground in the image – the striking red of the earth contrasting with the dazzle of wildflowers – and used a strong palette to achieve this. The finished tapestry has a buoyant sense of vitality and, in its mesmerising harmony between humanity and nature, represents a condition of perfection, an idyll.

Panjiti Mary McLean’s work has been collected by all major Australian institutions.

Rising suns over Australia Felix was the first of several tapestries designed by John Olsen AO OBE and woven by the ATW in 1997.

After working with tapestry workshops in France and Portugal in the 1960s, Olsen found the work of ATW weavers to be world-class and has been a steadfast supporter of the ATW ever since. Olsen is widely considered to be one of Australia’s most important living artists. He is known for his lyrical drawings and paintings that feature native Australian flora and fauna. His works are constructed with multiple meandering lines, energetic life-forms and the rich colours that make up the Australian landscape.

Rising suns over Australia Felix, commissioned by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, was inspired on a return flight to Australia, at the exact moment when Olsen witnessed a sunrise and saw the ascending orb gradually illuminate the expansive land below. The scene is split into two distinct halves – sky and land – but in both realms the surface is dappled, suggesting the luminosity of the dawn scene. The monumental scale of the tapestry effectively conjures the vastness of the Australian continent.

Olsen’s work is housed in Olsen Gallery and has been collected widely by national and international institutions.

It was a true honour for ATW weavers to translate Untitled, designed by Anmatyerre elder Emily Kame Kngwarreye into a tapestry in 1997.

Kngwarreye was born at the beginning of the twentieth century and grew up in a remote desert area known as Utopia, 230 kilometres north-east of Alice Springs, distant from the art world that sought her work. She came to painting later in life, producing over 3000 paintings in her eight-year career—an average of one painting per day.

The extensive body of work that she produced was inspired by her experiences as an Anmatyerre elder and her custodianship and dedication to the women’s Dreaming sites of her clan country, Alhalkere.

In 1997 ATW weavers Grasyna Bleka and Milena Paplinska had the exciting challenge of interpreting Kngwarreye’s complex visual language into a tapestry.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye's work has been collected by many major Australian and international art institutions.

Emily passed away on September 2, 1996. The ATW hopes that her tapestry will stand as a reminder of her significant contribution and creative legacy.

In 1996 Wamungku- My Mother’s Country, designed by Ginger Riley Munduwalawala, was translated into tapestry. Munduwalawala (c1937-2002) was a member of the Mara Community from the Gulf country in Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory.

For many years Munduwalawala worked as a stockman on Nutwood Downs Station and, while travelling, met the well-known Indigenous artist Albert Namatjira, an encounter that was to influence his artistic development.

Munduwalawala’s large-scale tapestry Wamungku, My Mother’s Country was commissioned by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in Canberra. The image is replete with references to Munduwalawala’s ancestral land on the Limmen Bight River in the Gulf country. The scene depicts a red sky and the symbolically important Four Archers, which represent hill formations in the Limmen Bight landscape, relating to stories of the creation myth. The image also includes animal totems such as kangaroos, snakes and sea eagles. One of the totems depicted repeatedly across the image –the white-breasted sea eagle – was the subject of an earlier, smaller tapestry woven by the Workshop. The sea eagle, known as Ngak Ngak in Munduwalawala’s native language, often appeared in his paintings as an emblem of vigilance, a totem keeping protective watch over his beloved homeland.

Untitled, designed by prominent American artist Frank Stella in 1996, proved to be a challenging and exciting project for ATW weavers.

Stella is an American painter, sculptor and printmaker, having worked through minimalism, hard-edge painting and post-painterly abstraction in his extensive career.

The tapestry design Stella produced for Untitled is a celebration of the bold colour and kaleidoscopic pattern and line-work that is now synonymous with Stella’s wider practice.

Stella’s work has been exhibited widely and is housed in many major international institutions.

The ATW was thrilled to weave Family Trust, designed by prominent Australian artist who was dubbed the bad boy of the Melbourne art scene in the 1970s-80s, Gareth Sansom.

Sansom’s painting has always been styled as a provocation to middle-class taste. His painting is expressionistic, replete with iconoclastic and sexually explicit imagery. Motifs from popular culture are interspersed with distorted figures and combined into a personal mythology: the canvases teem with manic energy, punk references and rebellious humour.

Family trust is an image brimming with contorted, spewing faces with disembodied eyes, all writhing in a patch worked pattern. The image is claustrophobic, packed with energy and agitated movement, and layered motifs jostling for attention.

Unlike most artists commissioned by ATW, Sansom did not desire active collaboration during the development of his tapestry. Once the design was finalised, he sought no further involvement in the tapestry’s evolution. However, after its completion he confessed that his curiosity had been so piqued that while the work was in progress he prowled around the Workshop at night, attempting to catch glimpses of the tapestry on the loom.

Family Trust is part of the ATW’s collection and was exhibited in a major retrospective of Sansom’s work, entitled Transformer, at the National Gallery of Victoria in 2017-18.

Sansom’s work has been exhibited widely in national and international institutions. He is represented by Milani Gallery in Brisbane.

Taking six ATW weavers almost 2 years to complete, the Aotea Tapestry, designed by Robert Ellis is a significant contemporary tapestry and one of the principle artworks in the Aotea Centre’s collection.

Ellis is a prominent British-born New Zealand painter who is concerned with social, cultural and environmental themes.

Speaking of the tapestry, Ellis noted: “It was not my intention to be too specific, as many people will prefer to interpret it in their own way. There are many different levels of meaning, depending on the viewer’s outlook.”

Robert Ellis’ work is held in many major institutions. He is represented by Milford Galleries in Dunedin.

In 1989 the ATW collaborated with John Coburn to produce St George tapestry, one of many works designed by Coburn and woven by the ATW.

John Coburn (1925-2006), more than any other Australian artist, displayed a true affinity with the tapestry medium. He lived and worked in France in the late 1960s and early 1970s, collaborating with the renowned French workshop Aubusson. The establishment of the ATW (then the Victorian Tapestry Workshop) allowed him to shift production and commence ongoing tapestry collaboration on home soil. The Workshop produced more than 25 tapestries based on Coburn’s designs, including works for Parliament House in Brisbane, National Australia Bank, Monash Medical Centre and many private and corporate collections.

In St George Tapestry, a commission for St George Building Society, Coburn wields his menagerie of anthropomorphic forms: a simplified vernacular of motifs like birds’ wings or fish tails, interspersed with abstract shapes. The composition is carefully constructed so that no forms overlap, but are arranged on a velvety ground as if they were object specimens laid for a naturalist’s view. Coburn’s curvilinear forms, however deceptively simple, posed a challenge for weaving.

John Coburn's works have been housed in major public and private collections, both nationally and internationally.

The ATW produced the monumental Great Hall Tapestry, spanning 9.18 x 19.9m, and designed by prominent Australian artist Arthur Boyd, for Parliament House in Canberra in 1988.

Boyd (1920-1999) is considered to be one of Australia's most distinguished 20th-century artists. He came from the Boyd dynasty of painters, sculptors, ceramicists and architects, and was part of the Angry Penguins school in the 1940s and later the Antipodeans, which included John Perceval and Charles Blackman. Boyd represented Australia at the Venice Biennale in 1958 and again in 2000. In 1979 he was awarded an Order of Australia, augmented by a Companion of the Order of Australia in 1992.

The design of Parliament House in Canberra was won by architect Romaldo Giurgola in 1979, and created the opportunity for the commission of a major public artwork. As an eminent living artist Arthur Boyd was offered the chance to produce an artwork that would cover almost the entire south wall of the Reception Hall. Extensive discussions ensued about the best medium to suit this scale, and tapestry was decided on as the ideal choice.

The tapestry design represents a forest of towering eucalyptus trees from the grounds of Boyd's rural retreat and studio at Bundanon. The tree-scape is quintessentially Australian, a homage to the majesty of the bush. Strong vertical rhythms structure the work, and the life-like proportions of the trees recreate the enveloping feel of a forest setting, fulfilling the architect's brief that the entire wall would almost appear as a three-dimensional living landscape.

The massive scale of the work - an astonishing nine meters in height and almost twenty meters in width - makes it the second largest tapestry in the world. It was woven in vertical sections by 12 weavers over a two-year period, and remains the most ambitious tapestry the Workshop has ever produced.

Arthur Boyd’s legacy is maintained through the Bundanon Trust collection and many major collections in Australia and overseas.

Woven in 1984, Roger Kemp’s Evolving Forms was designed to hang in the Great Hall of the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV).

Kemp was one of the earliest artists to work with the ATW. His visual language of symbolic forms made for a dynamic translation into tapestry. Kemp’s tapestry Images was commissioned in 1978 and acquired by the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) in the same year.

Evolving forms became the first in a suite of three tapestries designed by Kemp for, and conceived as a response to, the Great Hall and its extraordinary faceted glass ceiling designed by Leonard French. Both artists' works harmonise: the broad steel trusses of the vaulted ceiling, with its bright glass, find an echo in the charcoal bands that delineate the abstract forms and jewel-like colours of ruby-red, turquoise, lilac and amethyst-pink in Kemp's tapestries.

Roger Kemp was a major contributor to the development of abstract painting in Australia. His work is housed in major collections in Australia and overseas.

In 1982 four ATW weavers translated Pretty as - designed by prominent Australian artist Richard Larter - into tapestry.

Known for his use of bright colour and a collage-based approach to image production, Larter is classified as one of Australia's few highly recognizable pop artists.

Pretty as is housed in the National Gallery of Australia Collection in Canberra.

Larter has exhibited widely, both nationally and internationally, and is represented by Niagara Galleries, Melbourne.

Ring of Grass Trees, designed by Robert Juniper AM in 1978, was commissioned by the Friends of the Festival of Perth for Parliament House in Perth, Western Australia.

Juniper (1929 – 2012) was an Australian artist, art teacher, illustrator, printmaker and sculptor.

Juniper’s work is housed in several major Australian collections.

Marie Cook designed Wattle in 1979, as a companion piece to Pink Heath, woven in the same year for the Sofitel Hotel in Melbourne.

As oppose to Pink Heath, which was woven on it's side, Wattle was woven horizontally. This allowed more weavers to work on the project and facilitated the decision to purchase a new 8m loom for the Workshop.

Wattle and Pink Heath have remained popular depictions of Australian flora and are still much loved by Melbournians.

ATW weaver and artist Marie Cook designed Pink Heath specifically for the Sofitel Hotel in 1979.

The choice to weave the tapestry on it's side limited the number of weavers that could work on the piece. Five weavers took nearly one year to complete the tapestry and it was the Workshop's most time-consuming project to date.

Pink Heath was created alongside Cook's Wattle. The Cutting Off Ceremony for Pink Heath in 1980 was a europhic occasion, with all the weavers dressed in pink to match the tapestry.